Remember how in the nineties we had cockroaches at home, and when you lit the stove the floor turned red from them? I once stole money that you were saving up for winter boots and bought Snickers bars for all my friends, and then was too scared to go home and you had to go looking for me. And remember when the two of us lugged home eight bags of apples? We laughed the whole time, it was such great fun, and everyone was still alive back then. And the time someone was shot in the courtyard. The shots woke me up and I lay there in unbearable silence. I could hear them downstairs whispering about throwing the body in a lake. “Take his legs, I said take his legs, fuck.” And then silence again. Everyone around me was asleep so nobody else heard it. I was really scared, and you weren’t there anymore to tell you about it.

Thinking about Donetsk in the nineties is like looking at the sun from deep in the water: the light shifts and disappears, blurry shadows move above your head and you don’t know if what’s approaching are fishing boats or sea monsters and dragons that have risen from their mythical depths, ready to black out the sun and eat you up.

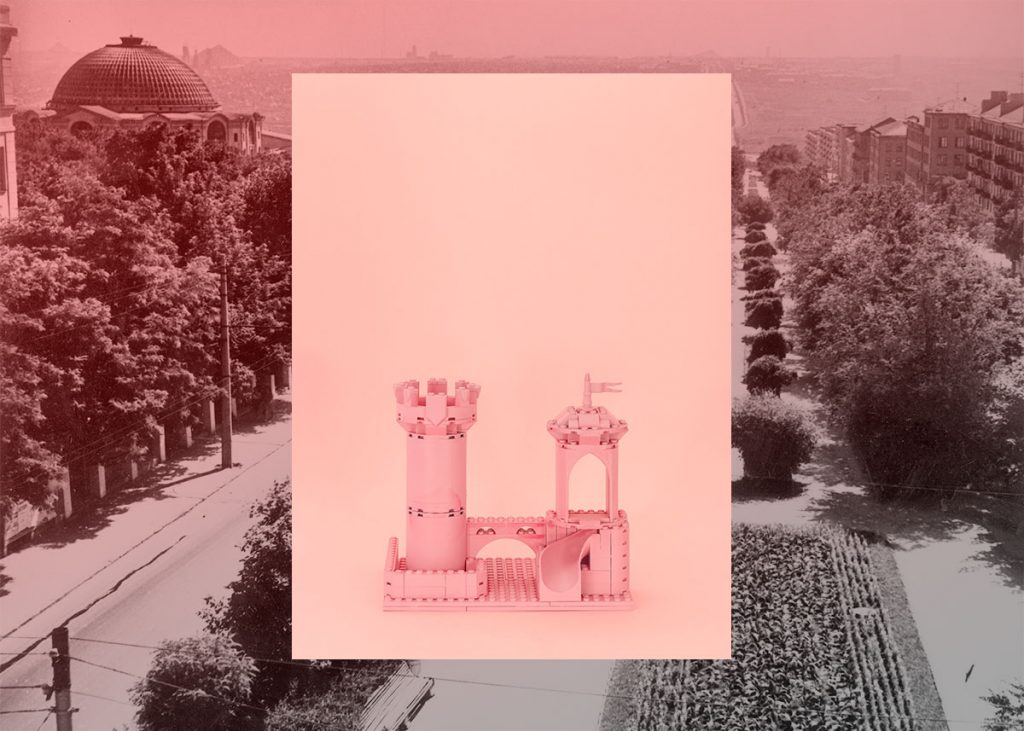

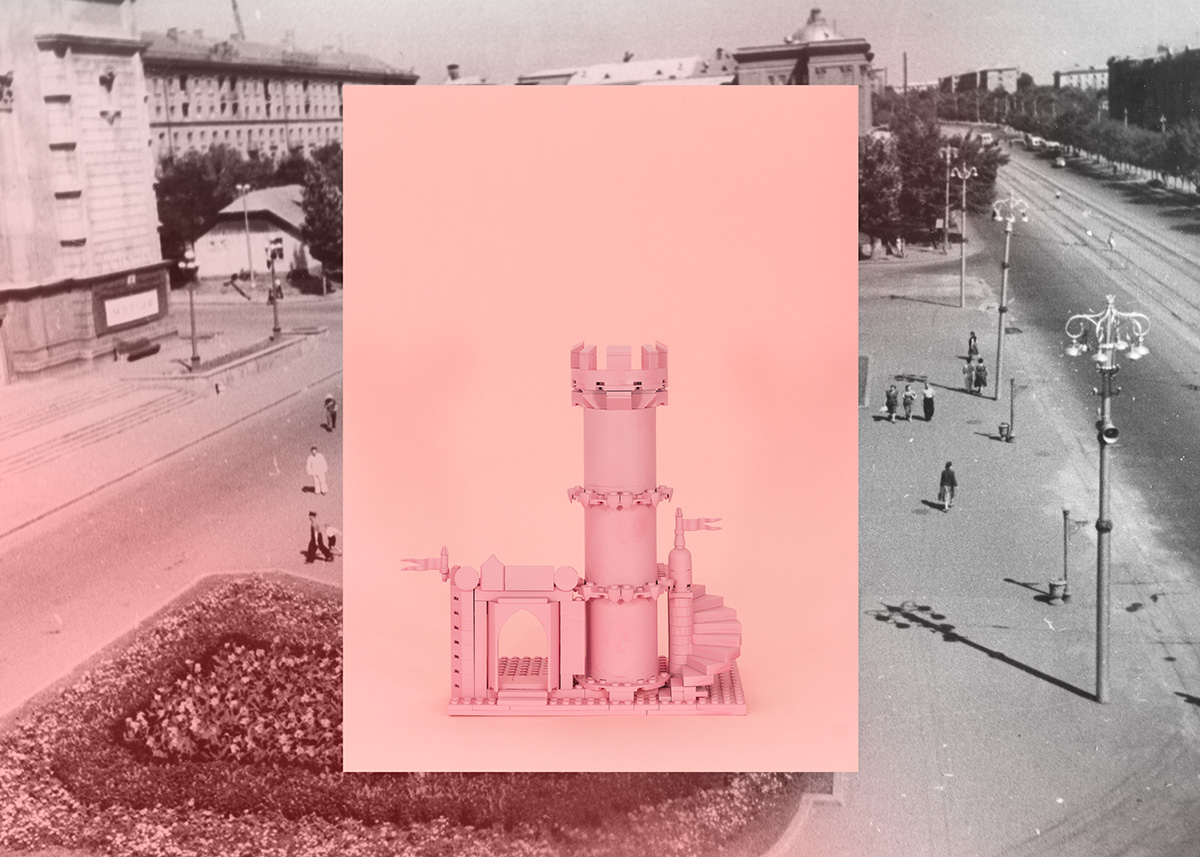

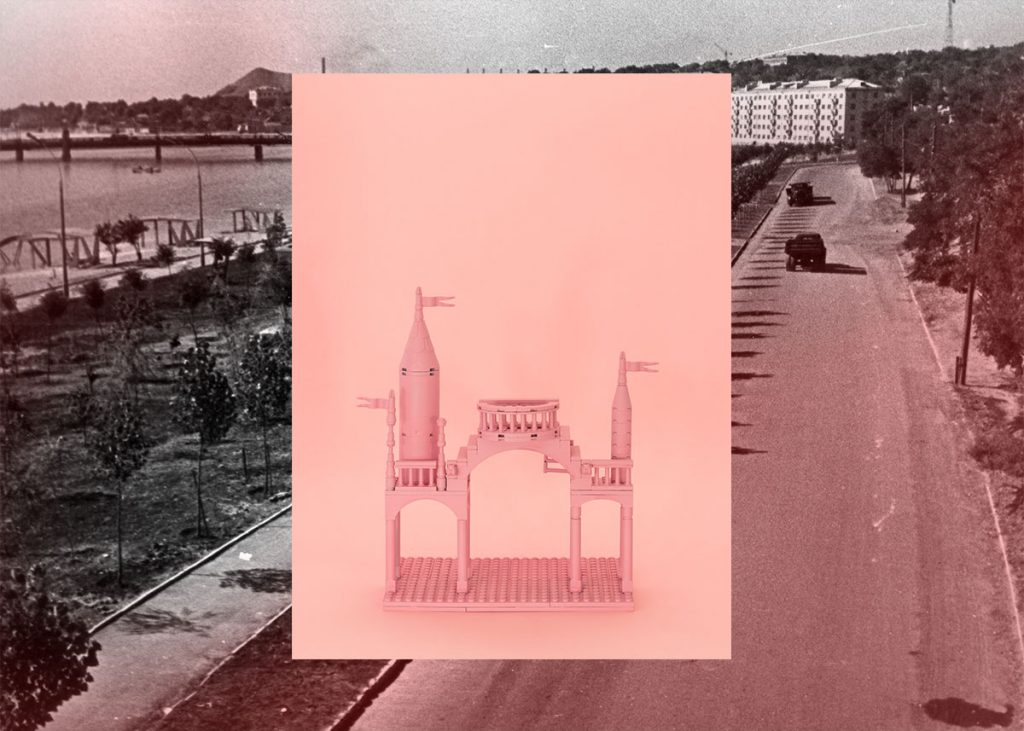

Mythologizing a place distant in time and space, and your own experience associated with this place, isn’t something unique to us, it happens one way or another with everyone. To analyze this process more deeply, we invited friends, acquaintances, and strangers to share their personal stories about Donetsk in the ’90s, the way they remember it. Lego bricks were used to make models of the places from their stories. These models aren’t perfect representations, but they help create an emotional and material connection with the past, serving as both a symbol and a tool of that connection.

Below you will find stories behind the castles:

A real fairy castle in Donetsk

Near the house we had just moved into there was a real castle! The whole inner courtyard was a playground for kids surrounded by a 1-2 meter high wall built of red bricks and granite blocks. Between the wall sections there stood six multi-storey towers and one of the passages was embellished with two small cannons – not real ones, of course, but nevertheless made of real metal. I was astonished back then, never before have I seen anything like that and I still have no idea how and why this castle was built there.

Справжній казковий замок в Донецьку

Коли ми переїхали, надворі, біля нашого нового дому був розташований цілий замок. Весь внутрішній двір був дитячим майданчиком, оточеним стіною один-два метри заввишки, яка була побудована з червоної цегли та гранітних каменюк. По периметру між секціями стіни були розташовані шість веж, які мали кілька поверхів, а біля одного з проходів були встановлені дві невеликі гармати — звісно, що не справжні, але відлиті з металу. Мене тоді все це дуже вразило, ніколи раніше я не бачив нічого подібного, але я й до сих пір не знаю, як цей замок там з’явився.

Lenin square under red-and-black flags

It happened sometime in 1990. We had just moved from the flat on Smolianka to the one somewhere close to Hvardiyka. One weekend we went to see cartoons at the video salon, it was a very popular service then. We were watching some Hollywood cartoons that they were simply playing on a TV set in a room. To get to this salon you had to take the seventh trolleybus, which went to Lenin square. The last stop was called Hurova, and from it you still had to walk up the avenue to the square itself. Next to the square, the terrain lies in such a way that when you are walking up you can barely see the square, because the climb there is very steep. You only begin to see the square a couple of meters from it, then it’s visible all at once.

And that time it was like that too, and suddenly, in the blink of an eye, we saw that the whole Lenin square is filled with people, and these people are holding red-and-black flags. The whole square was covered in these flags. I was six at the time, and I knew that there were red flags – because what other flags were there? I had never seen any other flags in my life. But these were red-and-black, and it was strange for me. My parents were surprised as well, we even stopped in front of the square. Then Dad said, “Ah, the nationalists!,” and we resumed walking at once.

Площа Леніна під червоно-чорними прапорами

Це сталося десь у 90-му році. Ми щойно переїхали з квартири на Смолянці в квартиру десь поблизу Гвардійки. Якось на вихідних ми поїхали дивитися мультфільми у відеосалон, тоді це була дуже популярна послуга. Ми дивилися якісь голлівудські мультики, які показували просто в кімнаті на телевізорі. Для того, щоб дістатися до цього салону, треба було сісти на сьомий тролейбус, який їхав до площі Леніна. Кінцева зупинка називалася Гурова, від неї ще треба було по проспекту піднятися до самої площі. Біля площі проспект має такий рельєф, що коли ти піднімаєшся, то площу майже не бачиш, бо там дуже крутий підйом. Бачити площу ти починаєш лише за декілька метрів до неї, вона відкривається тобі вся одразу.

Так було і тоді, ми підіймалися, і раптом, в одну хвилину, побачили, що вся площа Леніна заповнена людьми, і ці люди тримають червоно-чорні прапори. Вся площа була в цих прапорах. Мені тоді було шість років, і я знала, що прапори бувають червоні – бо які ж ще? Інших я в своєму житті не бачила. Але ці були червоно-чорні, і це було дивно для мене. Мої батьки теж були здивовані, ми навіть зупинилися перед площею. Потім тато сказав: “А, націоналісти!” і ми одразу рушили далі.

The bank, Petro Shitov, and other imaginary people of Donbas

In the mid-90s, if you remember, there was a monetary reform – coupons, which at that point didn’t cost anything, were being exchanged for hryvnias. The majority of banks in Donetsk at the time belonged to the so-called Donetsk elite, which consisted of guys who by that time hadn’t all put aside their soldering irons and taken off their tracksuits. Those were the guys that had a lot of money, and of course, they wanted to exchange all that money. But according to the rules, you could only exchange a limited sum of money at a time. Clearly, not all rules applied to these guys, they wanted to exchange all their money, and they had a lot of it. For that reason the cashiers at the banks had to make up imaginary citizens who were allegedly bringing that money, to sign for them, to make up names and surnames for them. At some point, maybe on the third or fourth day, those cashier women got bored and began making up various funny names to somehow amuse themselves, because sometimes their working shift would last for 20 hours. And so the lists gradually came to consist mostly of various Petro Shitovs and other even less appropriate surnames. It was fun, but at one point, when Petro Shitovs had reached critical levels, the women were uncovered by the bank administration.

And after a 20-hour shift of giving out the money the workers had to sit and rewrite those monstrous tomes of imaginary people, making up new, more appropriate people of Donbas.

Банк, Петро Говнов і інші уявні люди Донбасу

В середині дев’яностих, якщо ви пам’ятаєте, була грошова реформа – купони, які нічого вже не коштували, міняли на гривні. Більшість банків в Донецьку в ті часи належали так званій донецькій еліті, яка складалася з хлопців, які на той час ще не всі відклали паяльники і перевдягнули спортивні костюми. Це були хлопці, в яких було багато грошей, і вони, звісно, всі ці гроші хотіли поміняти. Але за правилами міняти можна було лише якусь конкретну суму готівки. Ясно, що не всі правила обходили цих хлопців, вони хотіли поміняти всі свої гроші, а грошей в них було багато. Тому касирам в банках доводилося вигадувати уявних громадян, які нібито приносили ці гроші, розписуватися за них, вигадувати їм імена і прізвища. В якийсь момент, на якийсь третій або четвертий день, жіночки знудилися і почали вигадувати різні кумедні імена і прізвища, щоби якось себе розважити, оськільки зміна їх часто тривала по 20 годин. Так списки поступово почали складатися переважно з різних Петрів Говнових і інших навіть менш пристойних прізвищ. Це було весело, але в якийсь момент, коли Петри Говнови досягли якоїсь критичної відмітки, жіночки були викриті керівництвом банку.

І після двадцяти годинної зміни видавання грошей працівниці були змушені сидіти і переписувати ці неймовірні талмуди з уявними людьми, вигадуючи нових, більш пристойних людей Донбасу.

A garage of baby soap

In the 1990s we had a full garage of baby soap. I don’t really know how it happened to be there, but supposedly the granddad got it instead of his salary. It was a frequent practice back then when they gave it in goods instead of money. The garage looked pretty standard – ‘rakushka’, a light metal shed in a garage cooperative on the outskirts of the town. But in addition to a Zhiguli car and some old junk, as one would expect, there lived several columns of grey boxes with baby soap. We would take it few packs at a time and bring it to live at home, on a shelf in the pantry, to the stockpiles of picked food, flour, and old fur coats eaten through by moths. The soap had sharp edges and a stamp saying “GOST.” I liked tracing it with my finger until it would wash off. Those stockpiles of soap were enough for three families for several years. I remember how surprised I was when one day it turned out that the garage-soap columns had run out and we had to buy soap, in my world, it was something virtually basic and imperishable.

What’s interesting is that mom absolutely could not remember the soap, but she remembers how we somehow came to be in possession of several blocks of cigarettes, which at the time were almost as good as currency, and we could then use them to pay various mechanics, plumbers, and electricians.

Гараж дитячого мила

У нас в девяностые был полный гараж детского мыла. Я не особо знаю, как оно там завелось, но вроде бы дедушке выдали зарплату им. Тогда это частая практика была, когда каким-то товаром выдавали вместо денег. Гараж выглядел довольно стандартно – металлическая ракушка в гаражном кооперативе на окраине города. Но кроме жигуленка и старого барахла, как положено, в нем жило несколько колонн из серых коробок с детским мылом. Мы его забирали по несколько упаковок и приносили жить домой на полку в кладовку, к запасам солений, муки и старым, поеденным молью шубам. У мыла были острые края и штамп с надписью ГОСТ. Мне нравилось по ней водить пальцем, пока не смылится. Этих запасов мыла хватило на три семьи на несколько лет. Помню, как я удивилась, когда однажды оказалось, что гаражно-мыльные колонны закончились и мыло надо покупать, в моем мире оно было практически чем-то базовым и нерушимым.

Интересно, что мама про мыло совсем не смогла вспомнить, зато помнит, как каким-то образом к нам попало несколько блоков сигарет, которые тогда котировались почти как валюта, и потом ними можно было расплачиваться с разными слесарями, сантехниками, электриками.

Shcherbakov park, hot-dogs in an abandoned amusement ride, and a bag of money

Like every Soviet person and citizen, I had a childhood friend named Lioha, me and him used to play together back in the kindergarten. Like me, Lioha decided to pass the winter of the ‘90s in Donetsk. Unlike me, he was enterprising and took up business – he opened a bar, where you could have a tea, drink vodka, and eat a hot-dog.

He picked the place and the time quite poorly and opened it in the winter in an abandoned pavilion of a bumper cars amusement ride in the deepest wilderness of Shcherbakov park. Except me, barely anyone would go all the way there, and I seldom did either, while Lioha would sit there all day inventing a Very Good Hot-dog, trying to reach the ideal. He experimented on me, and as a result, I grew fatter and was very happy. (Otherwise, I would not have grown fatter, nor have been happy – at that time I kind of had nothing to eat.)

But this is not about that and not about Lioha.

One day I came to him and was astounded to see a person in a hood there. He was standing in the corner humbly, holding two big bags. Lioha told me, “This here, Andy, is a person who is hiding from the bandits here. He has been hiding for already about twenty-four hours, and why don’t you take him under your wing.” I used to take everyone under my wing – I had a stupid love for random drunken intellectuals whom I used to fish out in the town late at night. And I took this Dima (figuratively speaking) too, of course. Turned out that one of Dima’s bags contained money, and the other, forged documents.

Dima earned his living by taking out loans or borrowing from the bandits, and never paying back. Then he would move to another town, take loads of loans there, and move to a third town. In Donetsk, he had taken out loads of loans, as usual, and it was precisely that moment when the bad guys started bothering him in terms of why don’t you, Dima, pay us a bit of money back. And so he went into hiding. At my place.

Dima would pay me for food $100 per 24 hours. I would take my hippie backpack, go to the shop called Maxim (it was the most fashionable store at the time), give them $100 and the hippie backpack, and tell them, ‘Fill it with food and beverages!” They knew me at the store and cheered as soon as I entered the door. $100 – that was a helluva lot then, and you could buy many different beverages from different countries for it. We would drink these beverages together with my artsy painter friends, who used to come to our flat in swarms. (Dima was very afraid of them at first, he’d sit in his hood and hide his eyes behind the black lenses of his sunglasses, but then he got used to them and began to enjoy it.)

And so I happily lived through the winter of the ‘90s, one the earliest ones, until the very spring, when one day Dima said, “Oh, they’ve found me!” (By the way, I still don’t know how he realized that – maybe he saw them through the window?) Anyway, Dima disappeared from my life, having bought a couple of paintings and left a certain sum of money as a farewell.

So I decided that he was killed. But no, it turns out – as I was told later – he vamoosed to the Baltic states with German documents. He lives in Germany now as a respectable burgher.

Lioha’s bar made it until the spring. Then certain people came and made him an offer he would have been happy to accept, but for which he could not pay, so his business withered away completely.

Парк Щербакова, хот-доги в закинутому атракціоні і сумка з грошима

У меня, как и у каждого советского человека и гражданина, был друг детства по имени Леха, мы с ним еще в детском садике играли. Зиму 1990-х годов Леха, как и я, решил провести в Донецке. В отличие от меня, он был предприимчивым и занялся бизнесом – открыл бар, в котором можно было выпить чаю, водки и съесть хот-дог.

Он неудачно выбрал место и время, и открыл его зимой в заброшенном павильоне аттракциона с автомобильчиками в самых дебрях парка Щербакова. Кроме меня туда редко кто доходил, и я тоже доходил редко, а Леха каждый день там сидел и изобретал Очень Хороший Хот-дог, стараясь достичь идеала. Свои эксперименты он проводил на мне, в результате чего я толстел и радовался. (Иначе я бы и не толстел, и не радовался – есть мне было в то время как-то нечего.)

Но речь не о том и не о Лехе.

Однажды я к нему пришел и с огромным удивлением увидел человека в капюшоне. Он скромно стоял в уголке с двумя большими сумками. Леха мне сказал – вот, Энди, имеется человек, который прячется здесь от бандитов. Он уже сутки примерно прячется, и не взял бы ты его под крылышко. Я всех брал под крылышко – у меня была дурацкая любовь к случайным интеллигентам, которых я ловил пьяными по ночам в городе. Я и этого Диму (условно говоря) взял, конечно. Оказалось, что в диминых сумках – в одной деньги, а в другой поддельные документы.

Дима зарабатывал себе на жизнь тем, что брал или кредиты, или в долг у бандитов, и никогда не отдавал. Потом он переезжал в другой город, набирал там очень много кредитов, и переезжал в третий город. В Донецке он набрал, как всегда, очень много кредитов, и как раз настал такой момент, что его начали тревожить нехорошие дяди на предмет того, что не отдал бы ты, Дима, немножко денег. Ну, он и спрятался. У меня дома.

Дима платил мне сто долларов в сутки на еду. Я брал свой хипповский рюкзак, шел в магазин Maxim (это был тогда самый модный магазин), отдавал сто долларов, хипповский рюкзак, и говорил – наполните мне его пищей и напитками! В магазине меня знали и радовались мне еще со входа. Сто долларов – это тогда было очень много, и на них можно было купить много разных напитков разных стран. Эти напитки мы выпивали с моими друзьями-художничками, которые набивались в нашу квартиру. (Дима их первое время очень боялся, сидел в капюшоне и прятал глаза за черными стеклами очков, но потом привык и втянулся).

Так я счастливо прожил зиму 1990-х годов, самых ранних, аж до весны, когда однажды Дима сказал – о, меня нашли! (Я кстати так и не знаю, как он это понял, может, в окно увидел?) В общем, Дима из моей жизни исчез, купив на прощанье пару картин и оставив некоторое количество денег.

Я так решил, что его убили. Но нет, оказывается – как мне потом рассказали – он слинял в Прибалтику по немецким документам. Сейчас он живет в Германии добропорядочным бюргером.

Лехин бар досуществовал до весны. Потом к нему пришли и сделали предложение, которое он бы и рад принять, но оплатить не мог, так что его бизнес совсем зачах.

Gurov Ave, Tower Café, and six pills of Taren

It began sometime in 1990-1991. There was a place in Donetsk – Tower Café. It was this kind of the centre of the universe because when you had nothing to do you would just go and sit there. It was an open café, you could have a Turkish coffee. There was Serhiy, the owner, he made good coffee. Or you could order nothing, just sit there – no one would mind. Everyone would meet there. I probably spent a few years there. Met everyone – whom I wanted to and whom I didn’t.

My daily schedule was as follows: we had a band with which we played, we would have a rehearsal, then we would go “to the Tower,” then to the ave, then at night we’d have about two or three bottles of vodka. It’s a very simple life.

Then there was that time when I lost all of my phosphorus. I met my friend whom they used to call Terminator (but it’s a different story why). We met, and he had Taren. It’s part of a military first aid kit – if you remember, there were those kits, and they each had six pills of this Taren. I was like, oh, this is cool, three for each! And we had already divided them, and we already had some wine or something else to wash it down, but then out of the blue, another guy appeared – “Oh, you have Taren! Let’s share.” We were like, “Okay!” Gave him one pill each. So each of us took two.

Half an hour later I was saying, “Thank God we didn’t take three!” Because it was the worst experience of my life. I cannot even explain or describe it. If you remember, Salvador Dali has this painting – this man with drawers sort of protruding out of him, that is, he’s completely made of drawers, there’re drawers sticking out of his chest, out of everything. So I was walking, like, my legs are here, my arms are here, and my stomach is somewhere two meters away from my legs. And no head! It lasted about three hours, it was very hard. It’s probably better than dying of phosphorus poisoning, but worse than anything else. It was something terrifying.

Since then I’ve never eaten Taren again. And all of those people died. And that guy, despite him being a Terminator, he also died.

Проспект Гурова, кафе “Башня” і шість таблеток Тарена

Десь у дев’яностому – дев’яносто першому році це почалося. В Донецьку було таке місце – кафе “Башня”. Це був такий центр всесвіту, тому що коли тобі було нічого робити, ти просто йшов туди і сидів. Це було відкрите кафе, можна було пити каву по-турецьки. Там був такий Сергій, хазяїн, він варив добру каву. А можна було й нічого не брати, просто сидіти – ніхто не заважав. Там усі зустрічалися. Я там провів, мабуть, кілька років. Познайомився з усіма – і з ким хотів, і з ким не хотів.

Мій распорядок дня був такий: у нас був гурт, з яким ми грали, була репетиція, потім ми йшли “на Башню”, потім на бульвар, потім вночі випивали десь дві-три пляшки горілки. Це дуже просте життя.

Потім трапилась історія, коли я втратив весь свій фосфор. Я зустрів свого друга, якого кликали “Термінатор” (але це інша історія, чому). Ми зустрілись, і в нього був Тарен. Це частина військової аптечки – якщо пам’ятає, були такі, і там шість таблеток цього Тарена. Я такий – о, це добре, по три! І ми вже розділили, і в нас вже було якесь вино чи ще щось запити, але тут як з-під землі взявся ще один хлопець – о, у вас Тарен! Давайте діліться. Ми такі – окей! Дали йому по одній таблетці. Тобто ми випили по дві.

За півгодини після цього я казав – слава Боже, що не по три! Тому що це був найгірший експірієнс в моєму житті. Я не можу навіть це пояснити і описати. Якщо пам’ятаєте, у Сальвадора Далі є така картина – такий чоловік, з якого висуваються як шухляди, тобто він весь состоїть з шухляд, в нього з грудей шухляди, все. Тобто я ходив такий, в мене ноги – тут, руки – тут, а живіт десь за два метри від ніг. А голови немає! Це було десь години з три, це було дуже важко. Це мабуть краще, ніж померти від фосфорного отруєння, але гірше, ніж все інше. Це було страхітливе щось.

З тих часів я ніколи більше не їв Тарен. А всі ці люди померли. А цей хлопець, хоч він і був Термінатор, теж помер.

The bridge over Kalmius river

The bridge over Kalmius river (though it’s not even a real river) is one of those nice places where people go to make pretty romantic photos: loving couples, girls against the evening sky, with the bridge in the picture – nice, sweet, romantic.

But the story is not about romance. A friend of our family had a son, a grown-up one. At some point, he fell off this bridge drunk – or maybe he was thrown off it, nobody really knows for sure – and drowned. It was a terrible tragedy for the family. They hired special divers who do this stuff for a living to pull the body from the river. And the divers started asking – what was he wearing, did he have any distinguishing marks? Show us his picture.

What are you talking about, what distinguishing marks, you’ve got to be fucking kidding – he lies dead in the river, isn’t that distinguishing enough, says the family. No way, it’s you who’s fucking kidding, answer the divers, tell us what was he wearing when he drowned or do you really expect us to pull every corpse from the river for you to see if it’s yours?

Міст через Кальміус

Міст через так звану річку Кальміус (хоча це й не річка ніяка насправді) – це таке красиве місце, де всі традиційно роблять такі гарні романтичні фото, ну там, закохані пари, або, скажімо, красиві дівчатка позують на тлі вечірнього неба, міст видно, красиво, гарно, романтично.

Але історія не про це. В однієї нашої знайомої був син, вже дорослий. Якось він п’яний впав з цього мосту – або ж його скинули, цього ніхто не знає – і втопився. Для родини це була страшна трагедія. Вони винайняли таких спеціальних водолазів, які займаються цього типу речами, щоб ті відшукали і витягли тіло. А вони й питають – а в чому він був одягнений, які особливі прикмети? Покажіть фото.

В сенсі – особливі прикмети, ви що, знущаєтеся, він мертвий на дні Кальміуса лежить, як на нас, це дуже особливі прикмети, відповідає родина. Блять це ви мабуть знущаєтеся, кажуть водолази, одягнений в чому був, чи ви думаєте, що ми кожного з річки будемо піднімати, щоб ви перевірили, чи це ваш?

Pigeon house

For years I had been collecting old paper for recycling. (In the late 70s and till early 90s, bookshops would only sell some of the more popular titles in exchange for a certain amount of paper for recycling.) It became a sort of habit for me. I was buying or exchanging where possible old books and eventually had amassed a pretty decent library. But some 20 years later these books had lost their value anyway.

Once, when I was out collecting old paper I had this chat with a drunk pigeon keeper. He said, “You are collecting old paper, therefore you might also steel from my pigeon house.” And I asked him, “What sense does it make to keep pigeons? Pigeons need to be taken care of daily and in any weather. A book is different. It waits patiently for me to have time to read it.” He just answered, “You understand nothing about this.” And he was right! I was never into smoking, drinking, and pigeons.

Голубятня

Я багато років збирав макулатуру. Для мене це була майже звичка. Де можна було купував книжки, де обмінював, і у нас на той час зібралась непогана книгозбірня художньої літератури. Але через пару десятків років ці книжки утратили цінність.

Як я збирав макулатуру, у мене була розмова з голуб’ятником, який був напідпитку. Він каже: “Ти збираєш макулатуру, так ти, напевне, і голубятню можеш обікрасти.” Я йому відповів питанням: “В чім привабливість тримати голубів? Адже за ними (голубами) потрібен каждоденний догляд при любій погоді. Друге діло книжка. Вона чекає, коли у мене буде час, щоб її читати.” Відповідь: “Ти в цьому нічого не понімаєш.” І це так! Голубами, палінням і випивкою я ніколи не займався.